A drug used to treat leg pain and prevent strokes could be repurposed to clear away the toxic amyloid plaques that accumulate in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients.

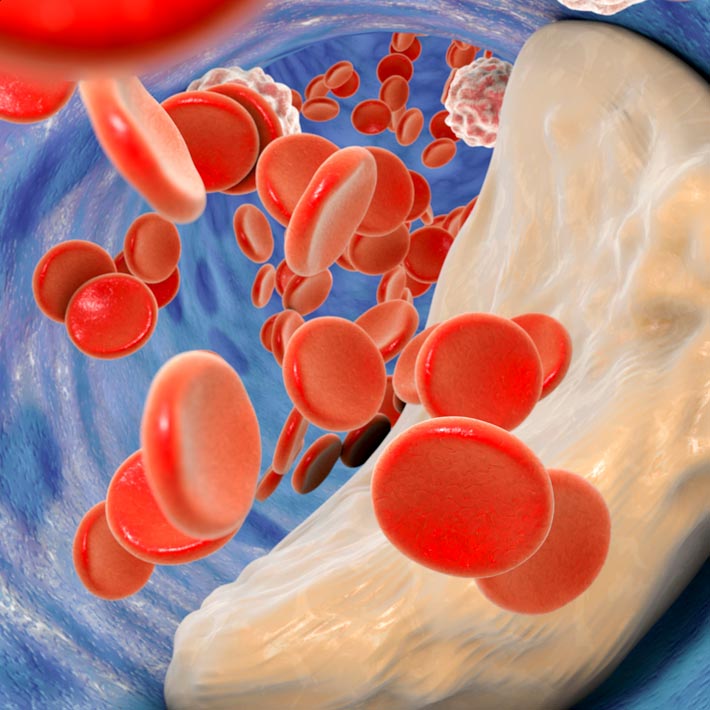

Alzheimer’s disease is closely linked to damage to the brain’s blood vessels, which leads to reduced blood flow. When the flow to the brain is reduced, lowered oxygen levels activate enzymes involved in amyloid production. Reduced blood flow also makes it harder to clear the toxic amyloid plaques away.

Cilostazol is primarily used to treat leg pain caused by a narrowing of the arteries that supply blood to the leg muscles. Besides dilating the blood vessels, it also reduces the ability of blood to clot, so some doctors also prescribe it as a preventative treatment for stroke.

Masafumi Ihara at the National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center in Osaka and colleagues previously tested cilostazol in mice models engineered for stroke, where they found that it maintained the integrity of blood vessels and reduced the amount of stroke-related tissue death.

Next, they turned to mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease — also associated with vascular damage. “We found that cilostazol increased the efficiency of amyloid beta clearance, significantly reducing the amount of it in the brain,” Ihara says.

To explore whether the drug might similarly benefit people with Alzheimer’s disease, in collaboration with Sumoto Itsuki Hospital, Hyogo, Japan, they studied the rate of cognitive decline among patients who had received cilostazol for leg pain or stroke prevention, compared to those who had started taking the drug but then stopped. It appeared to suppress cognitive decline — but only in patients with mild cognitive impairment; it was not effective in patients with more advanced dementia.

To confirm whether cilostazol really can slow the onset of dementia, Ihara, in collaboration with Japan’s Translational Research Informatics Center, is now running a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of the drug in approximately 200 mild cognitively impaired patients, who will be followed for 96 weeks. Besides testing their performance, he will also use brain imaging to assess the volume of the hippocampus — a brain area crucial for learning and memory, which usually shrinks as Alzheimer’s diseases progresses.

It’s a different approach to most other drugs currently in trials for Alzheimer’s disease, which target the production of amyloid beta. “Rather than trying to reduce amyloid beta production, we are trying to promote its clearance from the brain,” says Ihara.

References

- Saito, S. et al. A multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial for cilostazol in patients with mild cognitive impairment: The COMCID study protocol. Alzheimer's & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions 2, 250–257 (2016). | article

About the Researcher

Masafumi Ihara, Director of Neurology, National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center Hospital

Masafumi Ihara graduated from the Kyoto University School of Medicine in

1995, and undertook clinical training, before completing a PhD in Neuroscience

at the Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine in 2003. He received his

neuropathological training under the supervision of Prof. Kalaria in Newcastle

University, UK, and then led a neurovascular research group as an assistant

professor of the Department of Neurology in Kyoto University (2008-2012) and as a

deputy director of the Department of Regenerative Medicine Research in Institute of

Biomedical Research and Innovation (IBRI), Kobe (2012-2013). His research

interests have focused on the pathological changes in brain blood vessels and

how the alterations impact on brain health during old age.

Department of Neurology, National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center