Imagine medical researchers in Sweden being able to access data from anti-cancer drug trials in Kenya, which employ standards developed through global cooperation. That level of collaboration is still a long way off, but such a vision brought together researchers and medical administrators from around the world to the First Global ARO Network Workshop, held in Tokyo on 2 March 2017. The workshop was organized by Japan’s Translational Research Informatics Center (TRI), whose director, Masanori Fukushima, is pushing to establish Japan as a global hub for clinical research.

Clinical black hole

Billions of dollars are spent on clinical trials every year. But much of the data obtained gets obscured because it is collected in a wide range of formats that make it difficult to share and compare. This waste has been dubbed the black hole of clinical research.

In his opening remarks, Makoto Suematsu of the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development described the present state of affairs as a “balkanization” of information. Researchers are “living on the same planet, but not sharing ideas or data,” he said, likening the situation to a famous fight between American boxer Muhammad Ali and Japanese professional wrestler Antonio Inoki — despite great interest, the two made little contact because of the differences in their fighting styles.

There is little interaction, said Suematsu, between the many players involved in taking basic research to the clinic: gene sequencers and physicians, scientists and bureaucrats, and academia and industry. This leads to a great deal of wasted effort and replication. As a consequence, it takes an average of 17 years for findings in the lab to have an impact on healthcare — a delay that costs many lives.

TRI Director Masanori Fukushima fielding questions from the audience.

© Translational Research Informatics Center.

Standards and harmony

TRI organized the workshop in Tokyo to find global solutions to gaps in clinical research. This involves rethinking every aspect of clinical trials so that common standards are employed throughout the world. This could include developing standard patient agreement forms, streamlining protocols, using common terminology and definitions, and collecting data in formats that can be easily shared.

Keynote speaker, Rebecca Kush, of the Clinical Data Interchange Standards Consortium (CDISC) gave an overview of the global standards that CDISC have been developing and the advantages they offer, including a 70–90% reduction in start-up time. The CDISC has developed more than 30 disease-specific standards for therapeutic areas such as diabetes, oncology and virology.

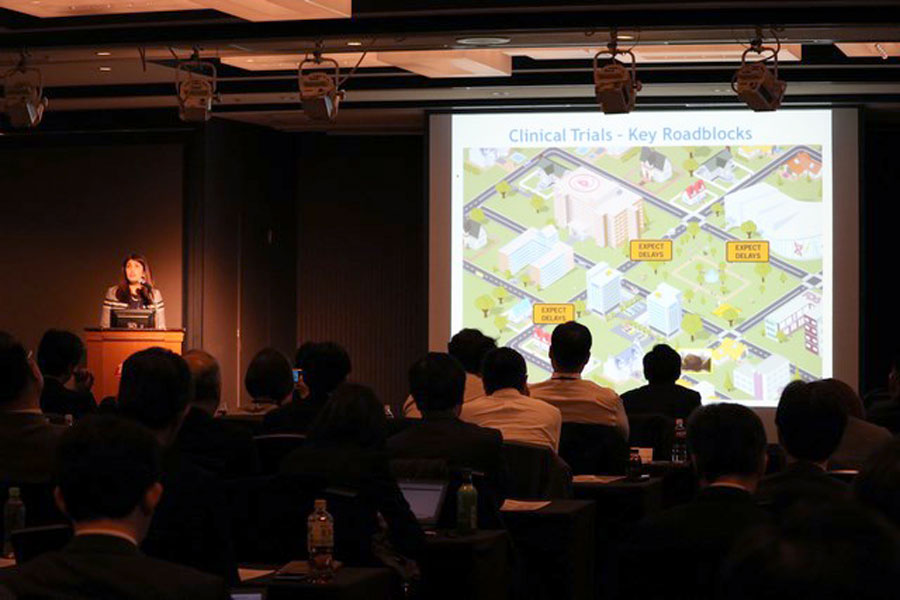

Monica Shah of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), which is part of the United States National Institutes of Health, described the Trial Innovation Network, a national, multidisciplinary platform that will enable clinical trials to be performed at multiple centers nationwide. It involves “rethinking the process of clinical trials” in order to “remove roadblocks and improve harmonization.”

Monica Shah of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) explaining how the Trial Innovation Network is seeking to harmonize the way clinical trials are conducted at different institutions.

© Translational Research Informatics Center.

Barbara Bierer of the Multi-Regional Clinical Trials Center of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard, spoke of the need to share data with the three major shareholders of clinical trials — study participants, researchers and the public — to make clinical trials safer for participants, as well as more rigorous and transparent.

Speakers from universities and centers in South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore and Japan talked about strategies their countries are adopting to realize global clinical trials as well as global networks to address specific diseases. Yoichi Nakanishi of the Japan Academic Research Organization Council spoke about the Japanese government’s strategy to promote clinical innovation, which has resulted in a dramatic increase in the number of patents from basic research.

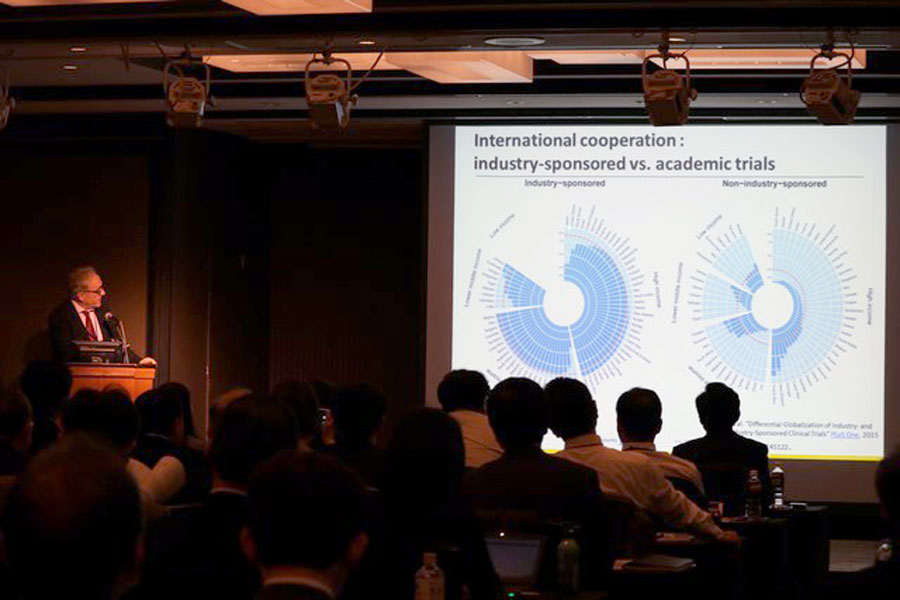

Jacques Demotes discussing standardization strategies adopted by the European Clinical Research Infrastructure Network (ECRIN).

© Translational Research Informatics Center.

In 2013, TRI established an Asia-wide network to promote standardization and harmonization in clinical research. “Science knows no borders,” said Fukushima in his closing remarks, urging participants to redouble their efforts.