The body’s own regenerative capacity can be stimulated to repair perforations in the eardrum by a simple outpatient procedure, Japanese researchers associated with the Translational Research Center for Medical Innovation have shown. They describe their research into this phenomenon in the TRI publication Principles of Regenerative Medicine.

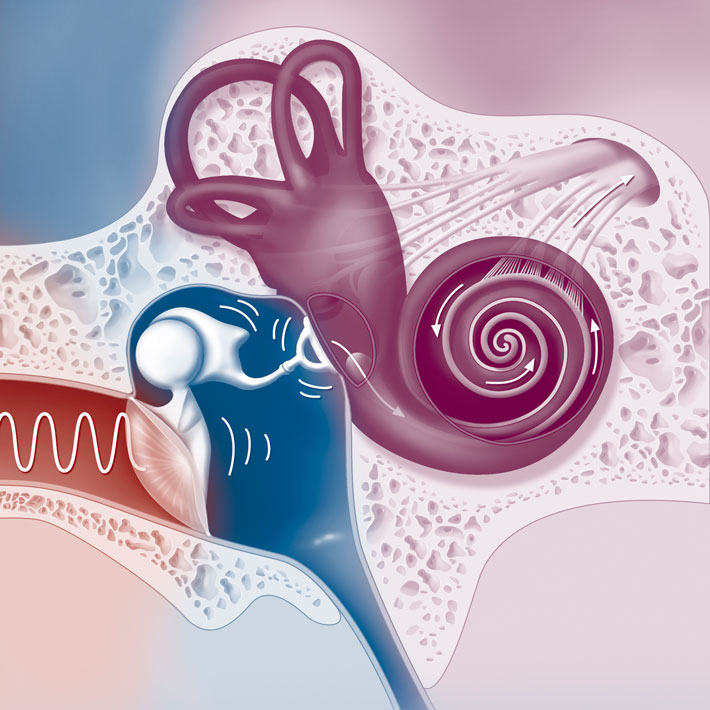

The eardrum can be perforated by various causes, including sudden pressure changes or puncturing by a sharp object. A perforated eardrum leads to hearing loss, which is a major contributor to dementia, and perforations also make the inner ear susceptible to infection. At least 330 million patients worldwide suffer from chronic infection of the middle ear, which is usually accompanied by a perforated eardrum.

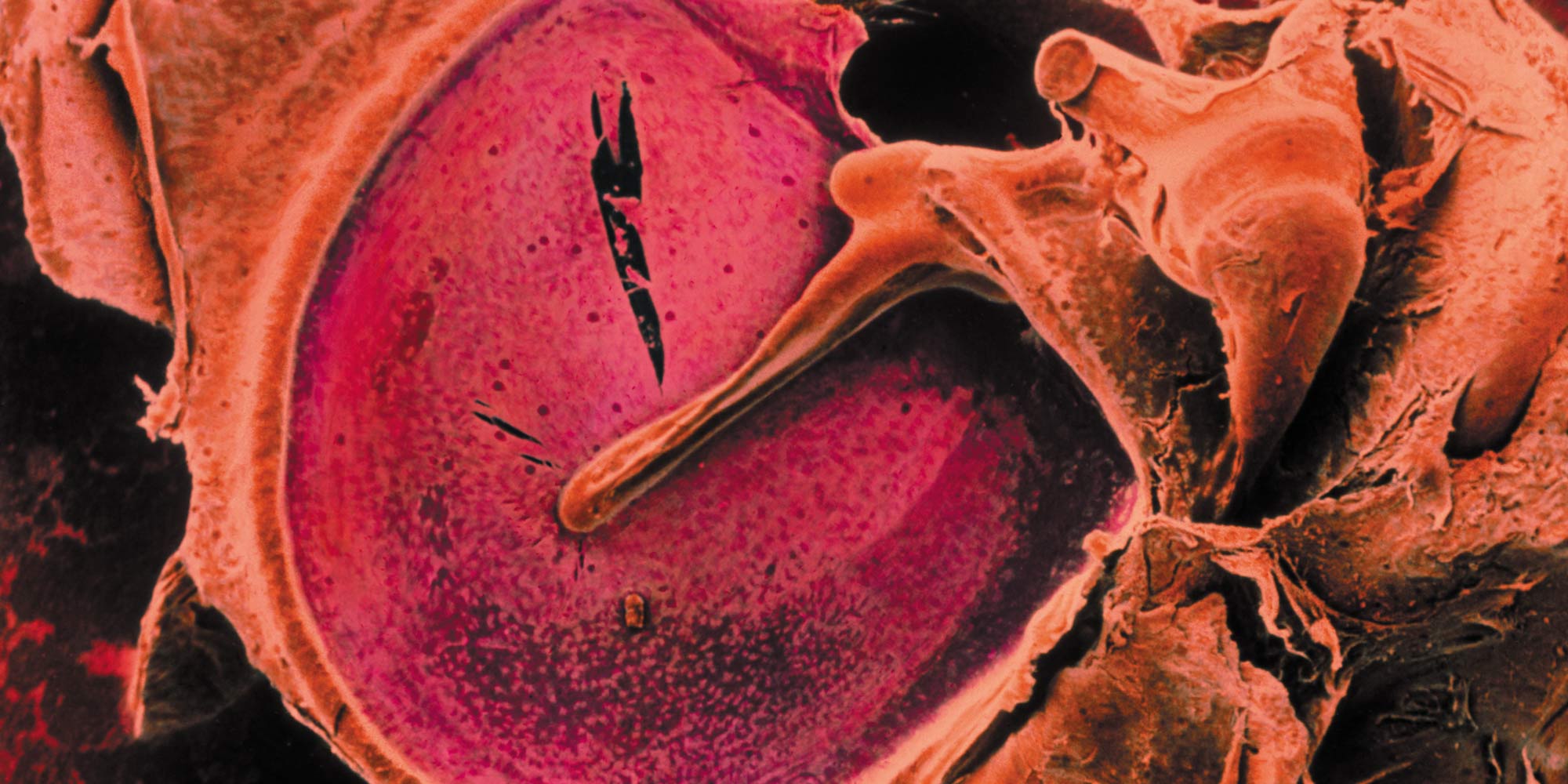

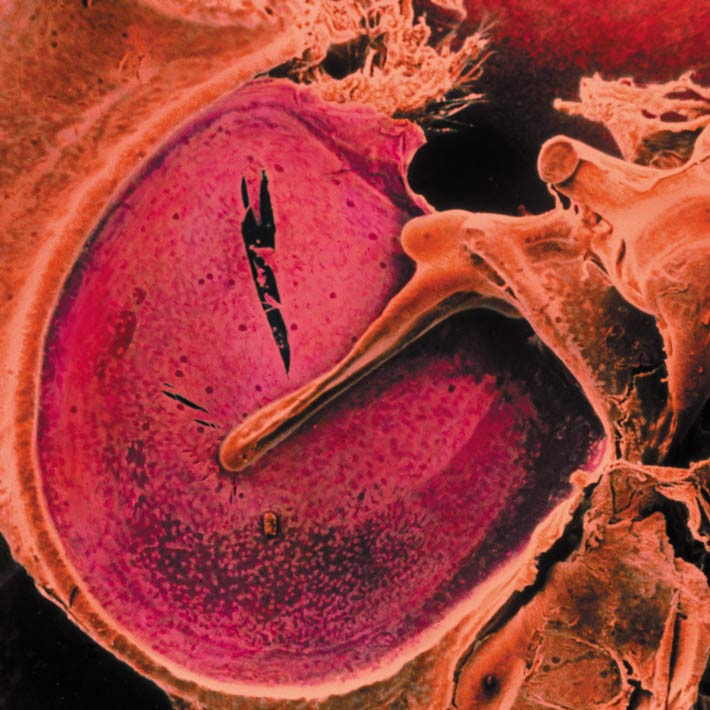

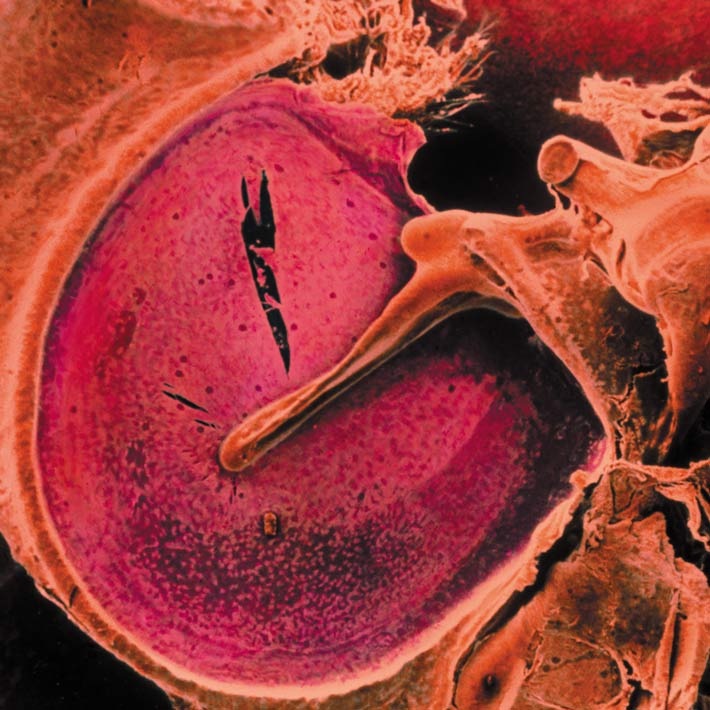

The eardrum, or tympanic membrane, has a natural capacity to regenerate. Simple perforations usually heal by themselves, with the injury provoking nearby stem cells into action. However, in infection and chronic inflammation these cells become dormant. Persistent perforations often require surgical treatment.

Shinichi Kanemaru from Kitano Hospital, Osaka, and other researchers associated with the Translational Research Center for Medical Innovation have developed a new tissue engineering approach. It involves activating dormant stem cells by enlarging the perforation. A gelatin sponge impregnated with basic fibroblast growth factor is trimmed to fit and placed over the hole. Gelatin has an advantage over the flat collagen sheets used in conventional regeneration therapies in that it can cover any perforation regardless of its shape or size. The loosely structured scaffold does not interfere with the expansion and movement of regenerative cells.

The sponge gradually releases the growth factor, which is a therapeutic product already available in Japan, thereby stimulating the regeneration of the middle fibrous layer of the tympanic membrane. It is this middle layer that is often poorly repaired in conventional procedures.

A single-center study of 218 patients showed a tympanic membrane perforation closure rate of 81%, with no more than two treatments needed in 80% of closures. No regeneration occurred in perforations due to burns or radiotherapy, and the researchers believe stem cells may have been absent in these patients. In a multicenter study of 20 patients, 80% of perforations closed within 4 weeks, and all patients exhibited improved hearing.

The researchers say a major advantage of this approach is its convenience compared to conventional surgical procedures, which are usually performed under general anesthesia and require specialized surgical training. In contrast, their therapy took only about 15 minutes and was performed in an outpatient setting. Kanemaru says the therapy can thus be easily applied in developing countries and may be attractive for older patients, who may have given up on treatment and are at risk of dementia.